![Comments on Recent Cases: March 2021]()

Parties frequently expect more from contractors than what their contract explicitly requires. Often they believe that the contract is a formality and the real agreement comes from their pre-contract discussions or common sense. This is not always the case.

Read More

![Representations and Warranties]()

Many contracts have “indemnification” provisions, that state exactly what a defendant needs to do if a representation is false. For example, the provision may state that the defendant is only responsible for a certain amount of damages or that the plaintiff needs to follow a specific procedure before it can bring a lawsuit.

Read More

![The Convention on the International Sale of Goods]()

Parties can determine whether the CISG is helpful for them or not based on whether they prefer its terms over the ones found in another applicable law. But putting those substantive differences aside, I believe that there is a significant benefit to the CISG, and a significant drawback.

Read More

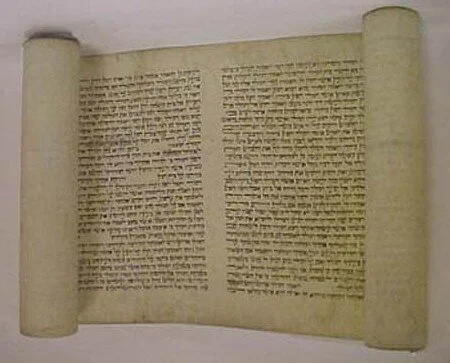

![Litigation in Jewish Rabbinical Courts]()

In some commercial cases, like employment cases with schools, our rabbis’ familiarity with the culture is important. And there are many situations in disputes where pure Jewish law applies and Beth Din judges have the competence to decide that in a way that secular courts don’t.

Read More

![Trial Exhibit Lists]()

The process for making an exhibit list often begins several weeks before a “pretrial conference” with the judge to discuss the trial. Often the judge’s rules or the court’s rules will instruct the parties to exchange proposed lists of exhibits. By exchanging these lists before the conference, the parties can identify the subjects of agreement ahead of time and then present their disagreements to the judge at the conference.

Read More

![Comments on Recent Cases: February 2021]()

People frequently sign non-disclosure agreements, promising to keep certain information confidential. Those agreements may not, however, prohibit a signatory from using that confidential information in a lawsuit. But to do so, the signatory may have to ask a judge’s permission to disclose the information privately to the court.

Read More

![I Don’t Know]()

The focus of a litigator’s practice is often not to advise clients how to comply with the law in the future, but whether an action in the past violated a legal obligation. And in many situations, virtually no litigator can say with confidence how the law applies to a dispute without a detailed study of various contracts and laws that govern the relationships between the relevant parties.

Read More

![Settlement Agreements]()

A defendant may be additionally concerned that someone may argue that the plaintiff’s allegations must be true since it agreed to pay money because of them. This is why many settlement agreements contain a statement that the defendant is not admitting liability, but is only settling with the plaintiff to avoid further litigation.

Read More

![Litigation in Israel]()

Israel does not have much evidence exchange before trial. The only requirement is that parties to a dispute are obliged to forward relevant documents to their counterparty. Then, after the last pretrial hearing, the judge usually orders the parties to file their evidence with the court by sworn affidavits.

Read More

![Direct Examination at Trial]()

According to an old adage, in cross examination the lawyer is the star, but in direct examination, the witness is the star. And so lawyers often draft questions so that the questions are short but the answers are long. Not only does this allow the judge or jury to focus more on the witness with firsthand knowledge than on the lawyer, but it also complies with a rule against “leading questions.”

Read More

![Comments on Recent Cases: January 2021]()

New York courts generally dismiss cases when the parties have agreed to arbitrate their disputes. But an exception may exist where the parties have litigated their dispute in court for awhile and then one party belatedly invokes an arbitration agreement.

Read More

![Bench Trials and Jury Trials]()

Commercial dispute plaintiffs in the United States often get to decide whether to have their claims decided at trial by judge or by a jury. Plaintiffs often select juries, because juries may be sympathetic to their claims. But there are also compelling reasons for a plaintiff to have a “bench trial,” in which the judge decides the facts of a case.

Read More