The First Steps in How Document Productions Get Made

Some details about the IT work involved in document productions.

As I discussed in an earlier post, litigants in New York and federal court are entitled to demand their adversaries and even non-parties produce relevant e-mails.

But how does someone take thousands of emails and decide which get produced? And are there a bunch of complicated rules and procedures that would surprise someone who doesn’t do this all the time? The answers are “a variety of ways” and “yes.”

Why should you continue reading this post about the first steps involved in making document productions?

Your lawyer told you that a document production may take a long time and you’re not sure why.

You’re an actor who is researching a role for a movie about document discovery that is only getting made as part of some The Producers-style fraud.

You’re in love and you don’t need to answer anyone’s questions.

Lawyers Upload All Custodian Emails into Document Review Software

As I discussed in a previous post, a lawyer responding to a document request works with her client to identify the “custodians", who are the people who may have sent or received relevant emails. The client sends the lawyer .PST mailbox files containing all of the custodians’ relevant and irrelevant emails.

PST files often contain thousands of files, most of which are irrelevant to the case. This is why lawyers use software to filter their client’s ESI.

There are several different software choices for lawyers to filter ESI. One popular choice is Concordance:

Concordance (Image Credit)

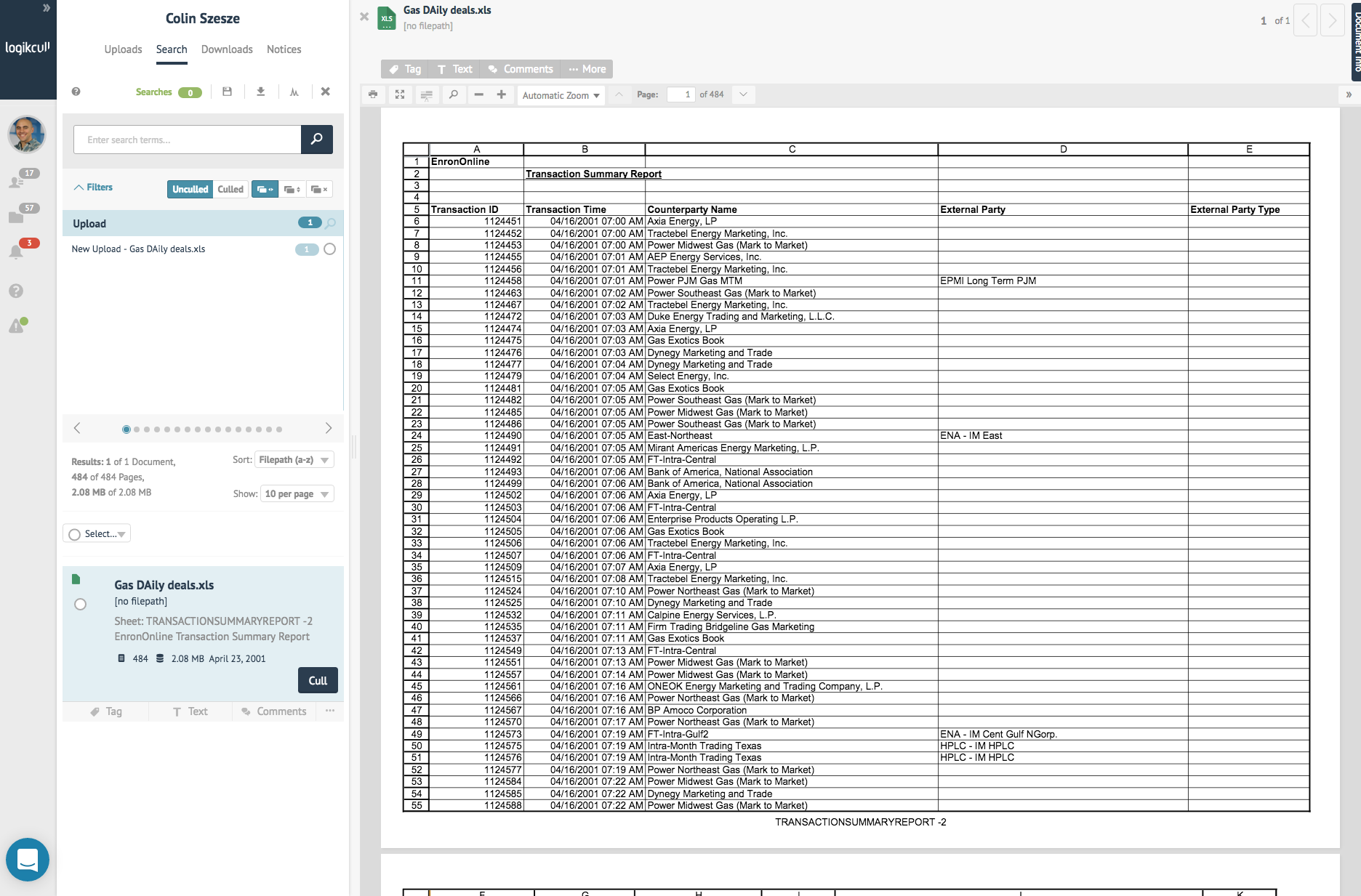

I have also heard of DISCO and Logikcull, but I have never used either.

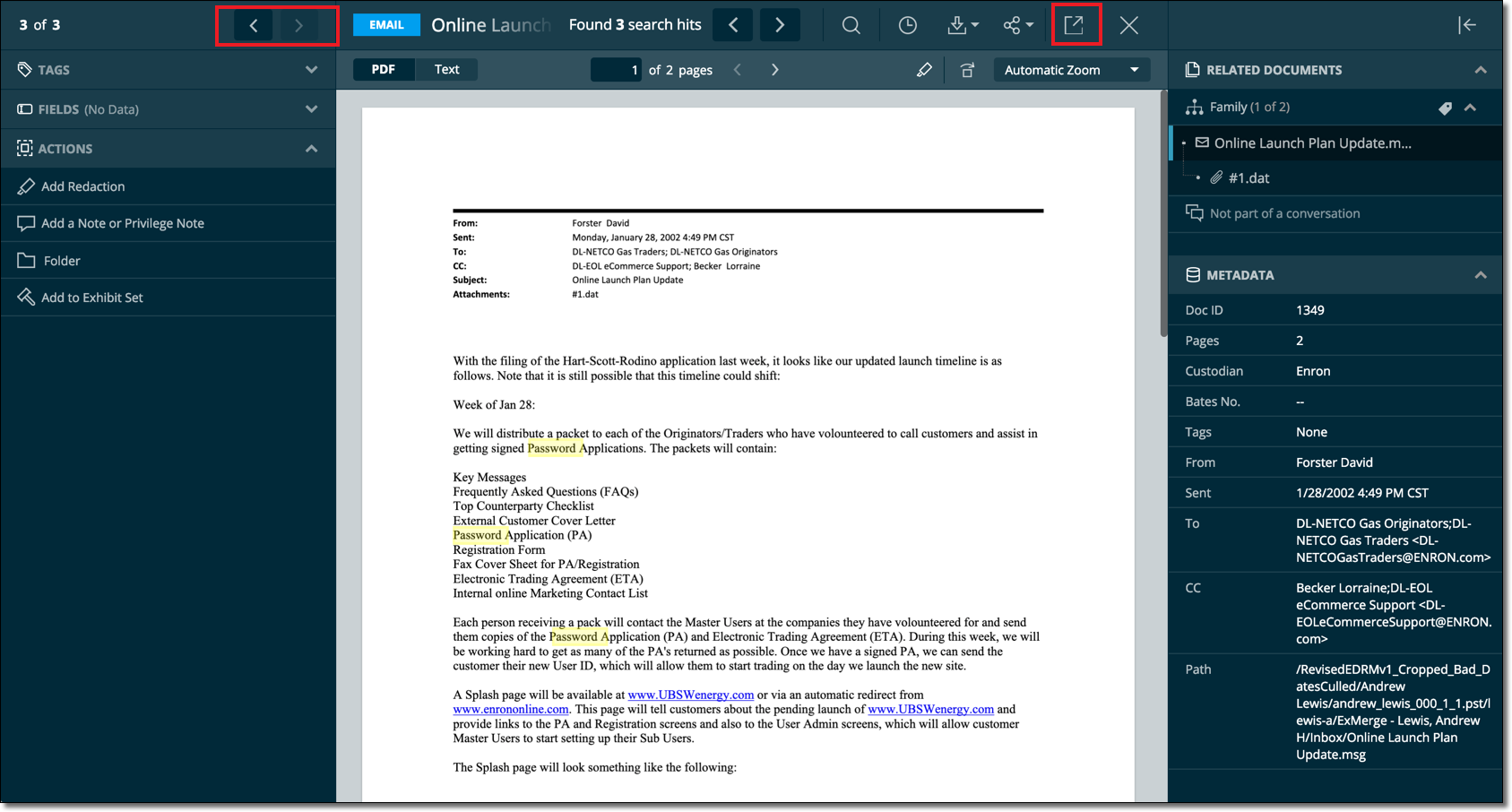

I have used three different pieces of software for document productions. One is Relativity, which is the standard in the industry:

Relativity (Image Credit)

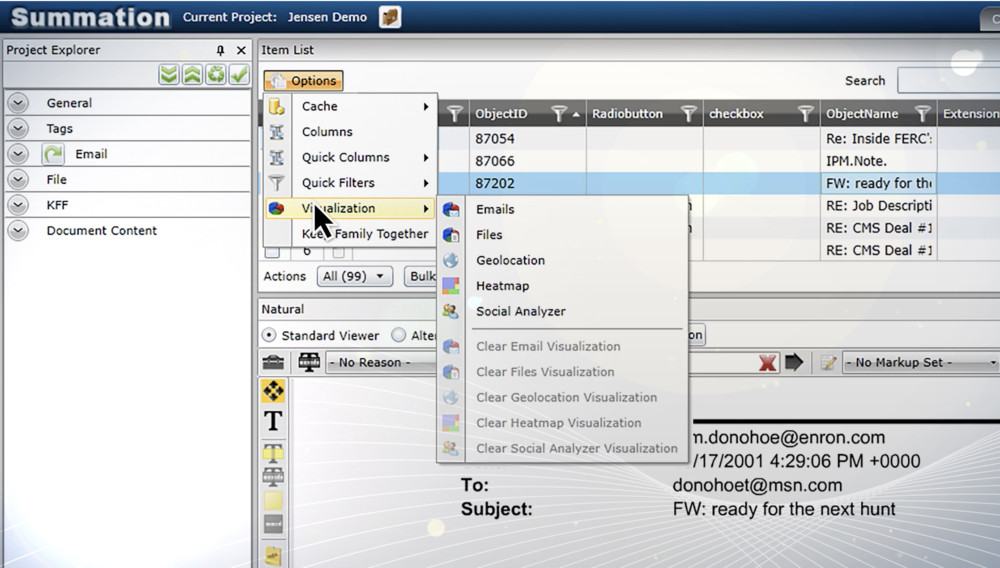

Another is Summation:

Summation (Image Credit)

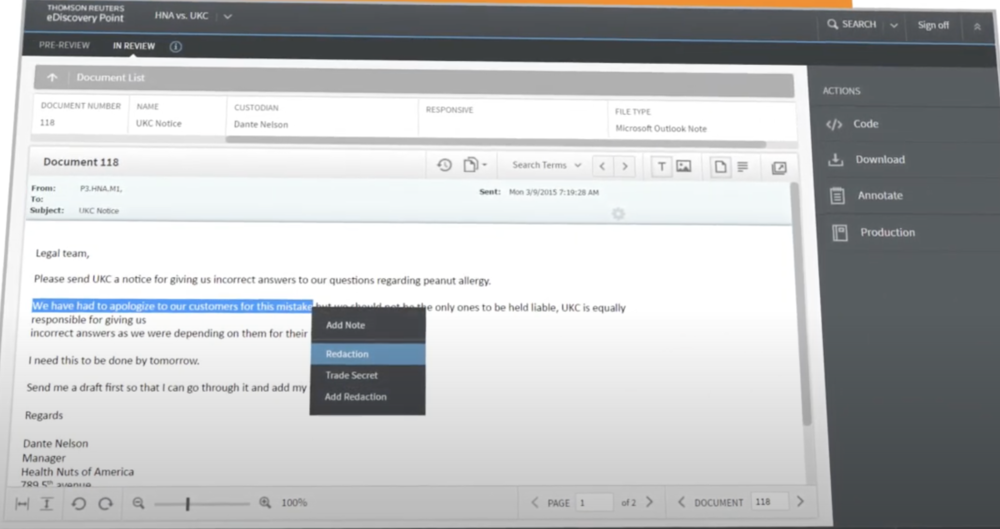

And the third one I have used is eDiscovery Point:

eDiscovery Point (Image Credit)

e-Discovery Software Can Filter ESI in Various Ways

Once client data has been entered into the software, it can be filtered in various ways.

The first thing the software may do is “deNIST” the ESI, which means remove files that the National Software Reference Library Project has decided are unlikely to contain relevant information. Examples of files that are removed in deNISTing are .exe files (which are computer programs) and .dll files because they are unlikely to contain information a witness wrote about the relevant facts of the dispute.

Next, the parties to a litigation may agree about the relevant time period for document discovery. If the dispute concerns the harassment of an employee who joined a company in 2018, then the parties may agree that emails from 2017 and earlier are irrelevant. Similarly, if a dispute concerns whether a bank knew that one of its account holders was engaged in fraud before 2010, then the parties could possibly agree that emails from after that date are irrelevant. e-Discovery software can filter out emails from outside of the specified date range.

Parties may also agree to search terms that can be used to filter documents that are more likely to contain relevant information than others. The requesting party will likely demand broad terms, while the responding party will insist on narrower ones. Making good search terms is an art, just as it is in case law research. But it does not determine which documents get produced, since a lawyer needs to review a document to determine whether it should be produced. Search terms only determine which documents will not get reviewed and thus not get produced.

But not every document that lacks a search term will be omitted from a document production. This is because when a document contains a search term, e-Discovery software will include its “family members” even if those files do not contain search terms. In this analogy, an email that attaches files is a “parent” and its attachments are the “children.” (Similarly, a .zip file is a “parent” and its compressed files are its “children.”)

Finally, e-Discovery software will “deduplicate” (or “dedupe” as cool e-Discovery people say) documents, filtering out exact duplicates so they do not need to be reviewed multiple times. Even so, in my experience, duplicate documents appear frequently in document reviews and document productions. This often happens when multiple people email the same document, or when people forward emails to other people, causing the forwarded email to be slightly different and thus not removed by deduplication.

Often, parties go back and forth on search terms, trying broad terms out, seeing how many documents respond to them, and adjusting them until the parties can agree on search terms that yield a manageable number of documents for the responding counsel to review.

Lawyers Then Review the Filtered Emails

Once e-Discovery software has filtered emails and other ESI, there are often thousands (often much more) documents remaining.

Someone (or something) needs to then review those documents to determine which need to be produced and which do not.

A law firm lawyer can review documents

Traditionally, the party’s lawyer reviews all of the documents. But this may be impractical for a few reasons:

It may take forever: In my experience, a person can review about 40 documents per hour. I can keep that pace up for about six hours a day, but some people can do as many as ten without evaporating from boredom. So if there are a hundred thousand documents, it would take over a year (including weekends, holidays, and allowing no time for any other work) to review all of the documents. Law firms have junior associates who can (and often do) handle this work, but they don’t have an infinite supply.

It may be expensive: Law firm lawyers cost several hundred dollars per hour. A 400+ hour document review performed by law firm lawyers may (and often does) cost over $150,000.

Lawyers can outsource document review

Many law firms outsource document review to contract attorneys, who are freelancers (who are licensed attorneys) who just review documents and code each to determine whether they should be produced. Outsourced document review is performed by lawyers so that sharing them with the reviewers does not breach the attorney-client privilege and require otherwise privileged documents to be produced.

Outsourcing is a better option for large review projects because e-Discovery vendors can convene a large team to review a lot of documents for a lower hourly rate than law firm lawyers would charge. I had a job doing this once and I got paid $40 per hour to sit in a windowless room with a bunch of other people for ten hours reading documents. After that project concluded, I declined an offer to return.

Although some document review projects take place in America, a popular trend is to have documents reviewed by attorneys in India, who charge lower rates than American lawyers. I have worked on a few projects with Indian document reviewers and have had generally favorable impressions of their work.

In any outsourced document review, however, the client’s attorney needs to spend time training the document reviewers on what the case is about and how they should decide what documents should be produced and which should not. The attorney must also review samples of the reviewed documents to make sure the reviewers are making correct decisions. And the attorney should tell the reviewers to pass to her any documents that are especially important or relevant (lawyers call these “hot” documents, which is kind of sad considering the fact that they are usually pretty dry) so that the attorney is aware of what evidence is good or bad for her case.

Lawyers can use AI software to review documents

Another trend is to use AI software to review documents instead of having people review them. This is called TAR, or technology assisted review.

I have seen presentations on TAR, but never used it myself. But my understanding is that an attorney personally reviews a sample of the documents and makes decisions about each. Then the software learns from those choices and reviews the remaining documents.

Lawyers code documents for responsiveness and privilege

Once a lawyer determines how she will conduct document review, the next step is to actually do the document review.

Assuming the lawyer has chosen to have people (as opposed to AI) review documents, over the course of days (or usually weeks), people will look at each document that survives filtering and “code” each for three things.

First, a person must code the document to see if it is responsive to a document request. Since document requests often have many parts, this may take awhile to determine. Only responsive documents (or the family members of responsive documents) get produced.

Next, a person must code the document to see if it contains any confidential communications between a lawyer and a client. If the entire document is such a communication, it may be withheld from production. If only a portion of the document is such a communication, it must be redacted so that un-redacted portions of the document may get produced.

And lastly, a person must code the document as a “hot” document if it is especially important for the case.

These are just the first steps in making a document production. I’ll discuss more in a later post.