More Thoughts on Complaints

Back in 2020, I wrote a post about the document that often starts a lawsuit: the complaint. My post focused on what complaints mean and how to read them. But I am updating the post to share some thoughts on strategy when drafting complaints, with the original post below.

Some complaints make the news. And so some people write complaints with extra details or explanations that may not be legally necessary, but because their audience is the public or reporters, they include them. So people who draft complaints may want to consider who the audience is and people who read complaints may consider whether the author was trying to win a lawsuit or public opinion.

If you read a lot of complaints, you may see some appear to have more details than others. And some appear more repetitive than others. A close read of these complaints may suggest how strong the factual case is: complaints that seem repetitive may indicate that the author is trying to obscure the fact she does not have much to assert her claim. Or it may suggest that the author paid little individual attention to the complaint, but instead filled out a form complaint that she uses for many different lawsuits.

A complaint is often an effort to prompt a settlement. Defendants and their attorneys often review a complaint to assess whether it looks like it states claims that pose a likelihood of success and whether the lawyers who drafted it seem sufficiently serious and intelligent lawyers to actually win a case or to negotiate reasonably. Complaints with clear errors or bizarre hyperbole may suggest that a negotiation would be unproductive or even unnecessary.

A major task in a complaint is to survive a motion to dismiss. One reason is because most cases settle to avoid the high costs and burdens of discovery, and so a complaint that proceeds to discovery is more likely to prompt settlement discussions. Another reason, of course, is because failing to survive a motion to dismiss means the plaintiff loses the case. And so lawyers draft complaints using specific language to meet the minimum legal thresholds to assert certain claims.

***

A lawsuit often begins when the plaintiff files a complaint. Its formal role is to notify the defendant about the subject of the lawsuit, but it may serve other roles as well.

Drafting a complaint is a complicated task. It requires legal research, storytelling skills, and some strategic decisions. A bad complaint could lead to a lawsuit being dismissed before discovery. A good complaint can prompt the defendant to settle on favorable terms.

Why should you continue reading this post about complaints?

You received a complaint and you’re curious about what the role of a complaint in a lawsuit is.

You draft complaints in another jurisdiction and you’re curious about how lawyers draft them in the United States.

You’re an artist who is looking in unorthodox places for inspiration

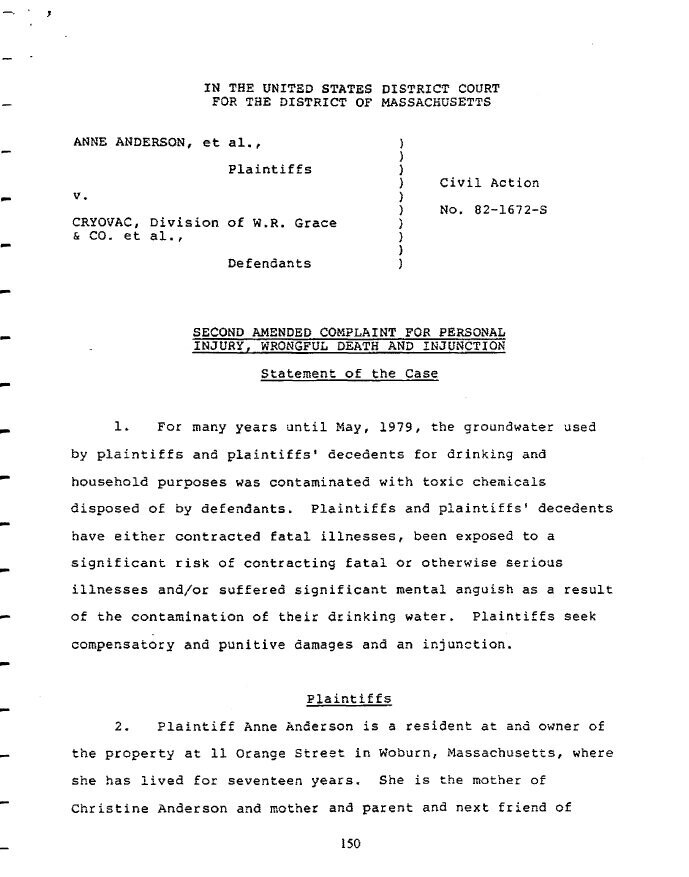

A complaint usually starts with the case caption and then sets forth the plaintiff’s allegations. (Image Credit)

Common Elements of the Body of the Complaint

The top of a complaint in American courts is the case caption. This tells the reader what court the case is in (or if it is not in court, what other forum, such as an arbitration body or government agency). It usually also tells the reader who the plaintiffs are and who the defendants are.

The bulk of the complaint are usually its factual allegations. This is where the plaintiff makes claims in numbered paragraphs that she believes entitle her to a judgment. The plaintiff does not need to submit evidence with the complaint to support the allegations. Normally, the plaintiff will only need to present evidence either at trial, or to avoid a motion for summary judgment after discovery. But rules like Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 11(b)(3) require a plaintiff to only make allegations if they have (or will have) evidentiary support.

Within the factual allegations, the complaint usually sets forth the basis for jurisdiction. Complaints in federal court are required to state this pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 8(a)(1). This is where the plaintiff explains why the court she has chosen for the dispute has the authority to decide the case. For example, a complaint may allege that a federal court has jurisdiction over a case because it arises from a violation of federal law and that it has jurisdiction over a defendant because she resides in the same district as the court.

A Complaint Needs to Set Forth Causes of Action and Seek Relief

Towards the end of a complaint, the plaintiff sets forth her causes of action (sometimes called “counts”). These are the specific laws or legal theories that the plaintiff contends entitles her to a judgment. A plaintiff will often allege multiple causes of action. For example, a plaintiff may allege that the defendant breached a contract, but also violated a labor law statute.

When a client tells a lawyer she wants to sue someone, she may not know all of the possible causes of action. She may just know that the defendant has done something wrong. It is up to the lawyer to use her own knowledge and research to determine what causes of action address the defendant’s conduct. This includes making sure that the statute of limitations has not expired for the applicable ones.

Each cause of action usually has elements that a plaintiff needs to establish to prevail. For example, to prevail on a fraud claim in New York, the Court of Appeals has held that a plaintiff needs to establish:

A material misrepresentation of a fact;

Knowledge of its falsity;

An intent to induce reliance;

Justifiable reliance by the plaintiff; and

Damages

To avoid dismissal, a lawyer needs to research the law to make sure the complaint alleges each of the required elements for its causes of action. So in this example, the complaint will need to allege facts that support each of these elements, and then state at the end that it is alleging fraud.

In a section at the end called the ad damnum, the complaint also needs to state what the plaintiff wants (also called the “relief” she seeks). In federal court, complaints are required to state the relief sought pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 8(a)(3). A lawyer may state the amount of money she seeks from the defendant and whether she seeks a court order addressing the defendant. Instead of stating a specific amount of money, the complaint may seek categories of damages, like money to compensate for the plaintiff’s loss or attorneys’ fees, in “an amount of money to be determined at trial.”

A Complaint Should Also Tell a Story

Although Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 8(a) says that a complaint needs only to set forth a “a short and plain statement” of the plaintiff’s claim and the other required elements, a good complaint should do more than that.

First, the Supreme Court held in Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly that a federal court may dismiss a complaint if it does not allege enough facts to meet a “plausibility” standard. These facts need “to raise a reasonable expectation that discovery will reveal evidence” that support’s the plaintiffs claim.

And second, a complaint is often many people’s introduction to the plaintiff’s claim. The media may find it and publicize it. The adversary will read it and decide whether she should settle the case. The judge and her clerks will likely read it and develop an impression about the case. As a result, a good complaint will set tell a story that describes a sympathetic plaintiff and a villainous defendant.

But a complaint need not be a novel. Extremely long complaints are difficult to read, as are repetitive ones. And although a complaint provides the plaintiff the opportunity to tell her story, motions for summary judgment and trial provide may fuller opportunities to set forth a narrative. And a plaintiff may choose to share some allegations in a complaint, but not others, because the plaintiff is aware that her understanding of the facts may develop as discovery progresses.