More Thoughts on Bench Trials and Jury Trials

In some trials, the judges decide the outcome. In others, a jury decides. Having spent even more time before each since my earlier post on this topic, I thought I’d update you on the differences between bench and jury trials.

“Bench trials,” in which a judge decides the facts of a case, make sense for cases with complex commercial issues. Judges tend to be more sophisticated in business matters and friendlier to business in general. Lawyers don’t need to worry about breaking down complex concepts in the same way they would to a jury. But there is a catch: Judges in some states are elected politicians, so they may have an eye on votes or political support in a way a juror does not. Another catch I have seen firsthand: Judges often apply their own understanding of technical concepts to decisions, and these preconceptions may be hard for a lawyer to account for in her arguments.

Juries make decisions harder to reverse on appeal. While a bench decision may need to state reasons that can be challenged on appeal, appeals courts are reluctant to overturn a jury decision if it has any valid basis, so a jury decision may be better for a party who wants finality.

Jurors often try to do what’s fair rather than focus on legal minutiae. When picking between a bench trial or a jury trial, litigants should ask themselves whether a random person could view their side as being unfair. Any corporation, employer, or rich or powerful person would be wise to accept that a juror may find it fair that they lose to a less powerful adversary, even if the adversary is legally wrong. Everybody loves an underdog.

It is not only hard to predict what jurors will do or who will be selected for a jury, but it is hard to predict who will show up on the day of your trial’s jury selection. You may expect a racially mixed jury from a diverse community, but that day a homogenous group of people showed up. It could be that you wanted a mix of young and old people and only got one generation. The random chance in jury selection cannot be understated.

Bench trials may be equally random in terms of the judge assigned to the case, and there is no room to address different points of view as with a jury. A lawyer puts her whole case’s decision on the shoulders of the judge to decide. One judge could see things very differently from another.

***

Commercial dispute plaintiffs in the United States often get to decide whether to have their claims decided at trial by judge or by a jury. Plaintiffs usually choose juries because they may be more sympathetic to the plaintiff’s claims. But there are compelling reasons to request a bench trial instead.

Why should you continue to read this post about bench trials and jury trials?

You want to serve on a jury, but criminal cases sound too interesting.

You want to know why litigants would have a private commercial matter decided by a jury of ordinary people.

You are curious enough about different kinds of trials to read a blog, but not so curious that you would ask someone out loud.

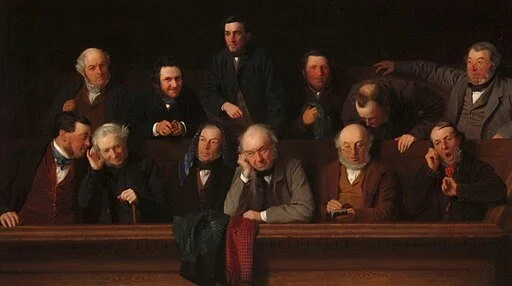

The Jury (oil on canvas) was painted by John Morgan in 1861 at the Assizes held in Aylesbury. This expressive work depicts 12 local men with varying expressions, sitting in the jury box. Each is identified in an accompanying plaque by his last name and profession. (Image Credit)

Why Plaintiffs Make Jury Demands

When a plaintiff files a complaint, the plaintiff may state that it demands a trial by jury. But just because it requests a jury trial does not mean that it will get one. The defendant may be granted a “motion to dismiss.” That is, the case may be dismissed before trial for a variety of reasons, such as a failure to state a claim or because the claims are barred by a statute of limitations.

But assuming a dispute proceeds to trial, a plaintiff may prefer a jury because jury of peers is likely sympathize with the plaintiff’s claims. If the plaintiff is a small business and the defendant is a large corporation, for example, plaintiff’s counsel may believe that jurors would identify more with the weaker party than the stronger one.

Additionally, if the plaintiff alleges that the defendant acted reprehensibly, such as by defrauding people or engaging in discrimination, the plaintiff may believe a jury is more likely to punish a defendant than a judge, who sees similar claims frequently and may be less disgusted by this one by comparison. This may make a jury more likely to find a defendant liable and more likely to demand that the defendant pay very high damages. The uncertainty in a jury verdict may pressure a defendant to settle rather than risk a high jury award.

A plaintiff may choose not to have a jury trial for various reasons. If the plaintiff is from outside the jurisdiction, it may fear the local jury pool will sympathize with the defendant. If the plaintiff is a big company, it may expect prejudice from an average jury—John Grisham didn’t get rich by making heroes of big, friendly corporations. And if the subject of the dispute is technical, the plaintiff may prefer a judge who has seen such cases before to evaluate the evidence.

Jury Trials Require Additional Work

Jury trials require a lot of extra work that may not go into a bench trial. First, the attorneys need to work together to select a jury. The attorneys interview potential jurors and may even hire a jury expert who can help decide which jurors are likely to support their case. Often, attorneys assemble pre-trial focus groups. It’s a kind of legal market research to determine which aspects of their case may persuade potential jurors.

Before trial, attorneys usually argue about what evidence the jury should hear, and the judge decides what evidence is likely to confuse the jury or what facts, irrelevant to the case, are too prejudicial for the jurors to keep an open mind. Attorneys will debate what instructions the judge should issue to the jury before they deliberate.

During the trial, the judge spends time instructing the jury. And some additional time is taken waiting for the jury to arrive, waiting again for them to walk from the jury room to the courtroom, and waiting for them to leave. Whenever the judge wants to speak without the jury present, for example, the public proceedings come to a full stop so the jury can file out of the the courtroom.

Attorneys at jury trials also need to be conscious of whether their presentation is holding the jury’s attention. Even the best evidence cannot persuade a juror who has fallen asleep. This may cause an attorney to cut out something that is dry or repetitive, or to present live arguments or testimony or graphic demonstrations that could have been more quickly presented on paper to a judge in a bench trial. Extra time adds to the cost of jury trials.

In the event the jury is unable to reach a verdict, there may be a mistrial, and the entire trial needs to start over with a new jury. In the event of an appeal, if the appellate court is unable to explain how a jury reached its verdict, the court may order a new trial.

Further, a litigant may ask the judge to decide that the evidence is so overwhelming on one side that a jury should not decide it, requiring the parties to debate that issue with the judge.

But Bench Trials Also Require Additional Work

Although bench trials do not require the lawyers to select a jury, or to stop and start when jurors file in and out, those trials also require additional work.

One additional step in a bench trial is the post-trial briefing. This is a written report for the judge that each side submits to signal which evidence at trial should lead the judge to rule in their favor, specifying exhibits and citing the trial transcript.

After post-trial briefing, the judge issues a written opinion explaining why she ruled for one side. That opinion may be a lengthy document, which may not be published until months after the trial ends.

Then each side carefully reads the judge’s opinion and decides whether any aspect of it is so mistaken that it is worth appealing. Although parties can also appeal jury verdicts, those appeals are more difficult since lawyers can’t know what evidence the jury relied upon to make its decision. Jurors are protected from having to reveal their discussions. Thus, an appellate court will usually uphold a jury verdict so long as some evidence in the record supports the verdict. But when a judge writes a detailed opinion explaining her reasoning, it is easier for an appellate to argue that the judge was mistaken.